Treatment for finger-bending disease may be ‘gamechanger’

Treatment for finger-bending disease may be ‘gamechanger’

Researchers have hailed a breakthrough in the treatment of a common, incurable disease that causes hand deformities by bending the fingers firmly into the palm.

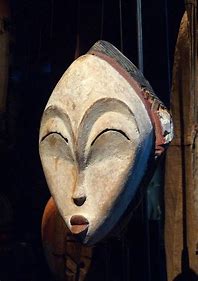

Provided by The Guardian Photograph: Fine Arts/Alamy

A clinical trial at Oxford University found that a drug used for rheumatoid arthritis appeared to drive Dupuytren’s disease into reverse when used early on, a result described as a potential “gamechanger” for patients.

“We are very keen to pursue this,” said Prof Jagdeep Nanchahal, a surgeon scientist who led the trial at Oxford’s Kennedy Institute of Rheumatology. “This is a very safe drug and it’s important patients can access a treatment if it’s likely to be effective.”

The disease is named after the French surgeon Baron Dupuytren, who besides claiming the honour of treating Napoleon’s haemorrhoids, acquired the arm of a dead man he had “kept an eye on”, not wishing to lose the opportunity to investigate his permanently retracted fingers. Dupuytren’s affects about 5 million people in the UK, half of whom have early stage progressive disease.

Dupuytren’s is largely genetic and more common in people with northern European ancestry. Though some call it the “Viking disease” there is no genetic evidence supporting a link. It often runs in families, but the exact cause is unclear with factors such as alcohol and tobacco use, diabetes, age and sex all seeming to contribute. Men are eight times more likely to develop Dupuytren’s than women and in western countries, prevalence rises from about 12% to 29% between the ages of 55 and 75.

“The problem for patients with bent fingers is they interfere with daily living: putting your hand in your pocket because it catches, putting gloves on, and it can be hard to use a keyboard, and even drive,” Nanchahal said. Though more common in the past, some patients with severe and painful Dupuytren’s still request amputations.

The disease is a localised inflammatory disorder that develops when immune cells in the hand drive the production of fibrotic scar tissue. This creates lumps or nodules in the palm. Sometimes the disease stops there, but it can progress, forming strong cords under the skin that steadily contract and pull one or more fingers into the palm.

The lack of an effective treatment for early stage Dupuytren’s means most patients are told to wait until their fingers are sufficiently bent to qualify for surgery. While the tissue can be cut out, there is a risk of nerve and tendon damage, and the disease returns in about a fifth of patients within five years. Another option is to use a needle to perforate and then snap the cord, but the cords typically grow back.

Writing in Lancet Rheumatology, the Oxford group describes how injections of adalimumab, a drug used for rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn’s disease, into nodules reduced their size and hardness compared with placebo injections. The volunteers received one injection every three months for a year. Follow-up examinations showed the lumps continued to shrink for nine months after the final injection. The drug, which costs £350 a shot on the NHS, blocks signals from immune cells which tell myofibroblasts to churn out fibrotic tissue.

“We know the effect lasts for up to nine months after the last injection, but assuming that at some point the nodule starts growing again, then if this were approved, the patient would come back for another four injections,” Nanchahal said. Similar injections could help to reduce recurrence of cords after needle or surgical treatment.

Nanchahal is discussing the data with the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency to understand what evidence they need to approve the treatment. Ideally, patients would be followed for 10 years to see whether adalimumab prevents hand deformities, but Nanchahal said this was not practical. “We have done the best we can in a patient population over a reasonable timeframe. We have measured everything we can think of,” he said.

Related: Certain gut microbes may affect stroke risk and severity, scientists find

Prof Chris Buckley, director of clinical research at the Kennedy Institute, said the drug could be a “gamechanger” and prevent the disease progressing to the point that patients need surgery.

Prof Neal Millar, an orthopaedic surgeon at the University of Glasgow, said the finding “could be hugely significant” in time. “This is a great step forward in understanding the disease, but longer-term evaluation is required if this is to be realised as a therapy,” he said.

Prof David Warwick, a hand surgeon specialising in Dupuytren’s at University hospital Southampton said: “Although these are early results, this is an exciting and important project because it addresses cell biology.

“Needles are simple and usually effective for a while, but the cord comes back. Surgery is usually successful but it takes a while to recover and occasionally there are problems. But supposing we can treat Dupuytren’s before it ever gets that far by addressing the cell biology? Now that would really change the world of Dupuytren’s.”

Reference: The Guardian: Ian Sample Science editor

No thoughts on “Treatment for finger-bending disease may be ‘gamechanger’”

Articles - Most Read

- Home

- LIVER DIS-EASE AND GALL BLADDER DIS-EASE

- Contacts

- African Wholistics - Medicines, Machines and Ignorance

- African Holistics - Seduced by Ignorance and Research

- African Wholistics -The Overlooked Revolution

- The Children of the Sun-3

- Kidney Stones-African Holistic Health

- PART ONE: DIS-EASE TREATMENT AND HEALTH-3

- 'Tortured' and shackled pupils freed from Nigerian Islamic school

- The Serpent and the RainBow-The Jaguar - 2

- PART ONE: DIS-EASE TREATMENT AND HEALTH-2

- PART ONE: DIS-EASE TREATMENT AND HEALTH-4

- PART ONE: DIS-EASE TREATMENT AND HEALTH-5

- King Leopold's Ghost - Introduction

- African Wholistics - Medicine

- Menopause

- PART ONE: DIS-EASE TREATMENT AND HEALTH-6

- The Mystery System

- The Black Pharaohs Nubian Pharaohs of Ancient Egypt

Who's On Line?

We have 93 guests and no members online

Ad Agency Remote

Articles - Latest

- The nightly ritual that could improve memory and brain health, according to scientists

- Hyacinth Bean: How Nutritionists Rate Its Nutrients, Health Effects, And More

- Top healthiest fruits with anti-inflammatory properties

- Vitamin B12 deficiency symptoms: How to spot the signs in your feet

- Dehydration may be as bad 'as smoking' for veins - how much water you need to avoid stroke

- Winter Squash: A Superfood Or Not? Nutrition Professionals Weigh In, With Serving Tips And Health Risks

- Why The Nutrition Professionals Love Winter Melon, Nutritional Benefits And Serving Size Guidelines

- Lesser-known lung cancer symptom in arm or shoulder that can't be ignored

- HIV breakthrough as new technology removes all traces of virus from infected cells

- Seven fruits for diabetics to avoid that can increase blood sugar spike risk

- Top 7 Uses and Benefits of Dead Nettle Plants

- 6 physical symptoms of anxiety you shouldn’t ignore, according to experts

- The five warning signs of bad circulation, according to a surgeon

- How to use wild garlic

- How many litres of water should you drink a day and does tea count?

- Cucumber: Nutrition Professional Opinions And Healthy Portions

- Hardening of the arteries speeds up ageing process, new study says - how to prevent

- FDA Approves First Gene Therapies to Treat Patients with Sickle Cell Disease

- Three questions for men facing infertility from risk factors to treatments