Michelle Obama recalls experiencing menopause symptoms as First Lady

Michelle Obama recalls experiencing menopause symptoms as First Lady

Michelle Obama has opened up about her experience of going through the menopause while First Lady of the United States.Michelle Obama has opened up about her experience of going through the menopause while First Lady of the United States.In the latest episode of her eponymous podcast, this time aptly titled What Your Mother Never Told You About Health with Dr. Sharon Malone, the author and lawyer candidly chatted to her 'dear friend', a Washington

DC-based gynaecologist about all things women's health – including the day-to-day impact her menopause side effects had.

Obama explained: 'I have a very healthy baseline, and also, well, I was experiencing hormone shifts because of infertility, having to take shots and all that. I experienced the night sweats, even in my 30s, and when you think of the other symptoms that come along, just hot flushes, I mean, I had a few before I started taking hormones.

'She then recalled one hot flush experience in particular: 'I remember having one on Marine One. I'm dressed, I need to get out, walk into an event, and, literally, it was like somebody put a furnace in my core and turned it on high, and then everything started melting. And I thought, "Well, this is crazy. I can't, I can't, I can't do this".'

Obama said it's time we ended the taboo around reproductive health, especially the menopause: 'What a woman’s body is taking her through is important information. It’s an important thing to take up space in a society, because half of us are going through this but we’re living like it’s not happening.'

The former First Lady said that her husband, former US President Barack Obama, also learned a lot about the menopause during his time in the White House.

'Barack was surrounded by women in his cabinet, many going through menopause, and he could see it, he could see it in somebody, 'cause sweat would start pouring. And he's like, "Well, what's going on?" And it's like, "No, this is just how we live," you know,' she explained.

'He didn't fall apart because he found out there were several women in his staff that were going through menopause. It was just sort of like, "Oh, well, turn the air conditioner on."'

Obama believes women need to be more honest about their reproductive health with men.

She said: 'How many men, do you think, could deal with the severest form of cramps? Which literally feels like a knife being stabbed and turned, and then released. And then turned! And then released.

'And you got to do that, and you got to get up and keep going [snaps]. It's like, go to work, go to school, go play on the basketball court. Every woman who's playing a sport now is doing it through all those circumstances. And I don't know any men who could possibly conceive of what that feels like.'

She added: 'When you think of all that a woman's body has to do over the course of her lifetime, going from being prepared to give birth to actually giving birth, and then having that whole reproductive system shut down in menopause, right?

The changes, the highs and lows, and the hormonal shifts, there is power in that. But we were taught to be ashamed of it and to not even seek to understand it or explore it for our own edification, let alone to help the next generation.'

Reference: Prima:Natalie Cornish 7 hrs ago: 13th August 2020

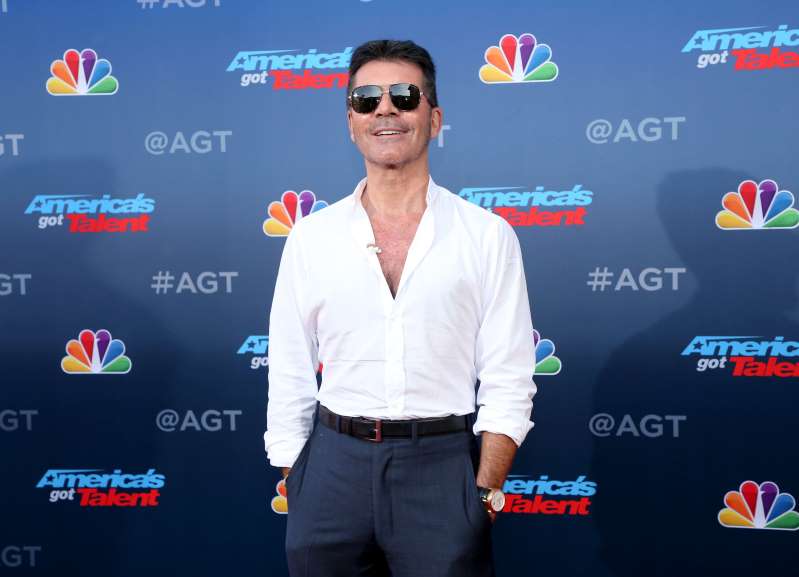

Simon Cowell updates fans in first tweet since breaking back in bike accident

Simon Cowell updates fans in first tweet since breaking back in bike accident

Simon Cowell has updated fans from his hospital bed after a biking accident which left him with a broken back.Simon Cowell has updated fans from his hospital bed after a biking accident which left him with a broken back.

The X Factor star was trying out a new electric bike at his Malibu home with his family when the incident occurred on Saturday (8 August).

The 60-year-old took to Twitter after surgery in the early hours of Monday (10 August) to reassure his 11.3million followers.

The music mogul jokingly recommended that people “read the manual” when trying out a new electric bike, and also praised the the medical experts who treated him.Cowell tweeted:

“Some good advice... If you buy an electric trail bike, read the manual before you ride it for the first time. I have broken part of my back. Thank you to everyone for your kind messages.”

He added: “And a massive thank you to all the nurses and doctors. Some of the nicest people I have ever met. Stay safe everyone. Simon.”

Following Cowell’s six-hour emergency surgery, Good Morning Britain’s, resident medical expert, Dr Sarah Jarvis warned he is likely to “have long road to recovery”.

And a massive thank you to all the nurses and doctors. Some of the nicest people I have ever met.

Reference: Yahoo: Danny Thompson 7 hrs ago: 8th August 2020

Mass thermal ‘ineffective’ in limiting spread of Covid-19

Mass thermal ‘ineffective’ in limiting spread of Covid-19

Mass thermal screening is “ineffective” in limiting the spread of Covid-19 because of asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic cases, research has found.Mass thermal screening is “ineffective” in limiting the spread of Covid-19 because of asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic cases, research has found.

Evidence published by the Health Information and Quality Authority (HIQA) shows that screening programmes using non-contact devices were not found to be effective in identifying infectious people and limiting spread of disease.

The detection rates, it said, were consistently low across studies.

HIQA looked at whether non-contact thermal screening could be used to effectively identify cases of Covid-19.

It has urged the Government to give “careful consideration” to the cost-benefit of such measures.

Our new evidence summary on non-contact thermal screening found that mass thermal screening programmes, using non-contact devices, at airports were not effective in identifying people with #COVID19. Read it here: undefined

HIQA identified 11 primary studies, three rapid reviews and one systematic review relating to Covid-19 and other respiratory virus pandemics.

The studies were conducted in the context of points of entry, including airports, so their relevance to other community settings, such as schools, is uncertain.

The evidence summaries were developed by HIQA following requests from the National Public Health Emergency Team (NPHET) Clinical Expert Advisory Group.

The evidence suggests that thermal screening is resource intensive and, due to a high proportion of asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic cases, results in low detection rates.

— HIQA (@HIQA) August 6, 2020

Dr Mairin Ryan, HIQA’s deputy CEO and director of health technology assessment, said: “Thermal screening has been used in other respiratory infectious disease outbreaks, such as the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic (swine flu) in Asia and Australia, to improve detection and reduce the time to isolation of infected individuals.

“It typically involves a combination of fever screening, such as temperature testing, alongside self-reporting of exposure risk and or symptoms.

“However, the evidence clearly shows that this type of test is likely to be ineffective in limiting the spread of Covid-19.

“Thermal screening is noted to be high cost and resource intensive. Detection rates are very low due to large proportion of cases that have no symptoms, are infectious before showing any symptoms or who do not present with fever.”

The HIQA also published its evidence summary on the immune response, and potential immunity, following infection with Covid-19 or other human coronaviruses.

We have also updated our evidence summary on the immune response, and potential immunity, following infection with COVID-19 or other human coronaviruses.

The research reveals that it is unclear whether long-term immunity to Covid-19 is possible.

Dr Ryan added: “Covid-19 antibody was detected in nearly all individuals up to three months after they were infected, and over 90% of patients had developed a neutralising antibody response, which protects against viral infectivity.

“However, a handful of new studies suggest that it may be possible to be reinfected with SARS-CoV-2. HIQA will continue to monitor the evidence on immunity and update our summary as required.”

Reference: PA Media: 10th August 2020 :By Cate McCurry, PA 3 days ago

Indian temple reports huge coronavirus outbreak as cases surge

Indian temple reports huge coronavirus outbreak as cases surge

MUMBAI/NEW DELHI (Reuters) - A well-known Hindu temple in India has seen more than 700 cases of the novel coronavirus among its staff in the past two months, a temple official said on Monday, as cases in the country surged past 2.2 million.MUMBAI/NEW DELHI (Reuters) - A well-known Hindu temple in India has seen more than 700 cases of the novel coronavirus among its staff in the past two months, a temple official said on Monday, as cases in the country surged past 2.2 million.

India reported a near-record 62,064 new cases of the virus in the past 24 hours, according to federal health data released on Monday, taking its total number of cases to more than 2.2 million.

India has fewer cases than only the United States and Brazil, though it has reported a relatively low number of deaths, at fewer than 45,000, although epidemiologists say the peak of its outbreak could be months away.

Cases in India have been spreading from urban areas to smaller towns and the countryside, where health infrastructure is already over-burdened.

The Lord Venkateswara temple in the town of Tirumala in south India, one of the biggest and most wealthy Hindu shrines in the world, said two of its staff and one former employee had died of COVID-19 since June 11, when it reopened to the public after a government lockdown.

In all, 743 temple employees had been infected by the virus, it said.

"We are providing the best medication to those infected. We are taking utmost precaution, social distancing norms are followed, devotees and others are wearing masks," said the chairman of the temple's trust organisation, Y. V. Subba Reddy.

It was not clear how many of the temple's thousands of daily visitors had contracted the virus.

The trust employs about 22,500 workers including 300 priests and controls 10 temples, including the main Venkateswara temple where it employs 36 priests.

India started a phased re-opening after a strict lockdown that was imposed on March 25. Temples and other places of worship were allowed to open in June.

Places of worship draw many thousands of people in India and premises are often cramped, making social distancing difficult.

(Reporting by Nidhi Verma in New Delhi and Shilpa Jamkhandikar in Mumbai; Editing by Alasdair Pal)

Reference: Reuters: By Shilpa Jamkhandikar and Nidhi Verma 5 hrs ago: 10th August 2020

Articles - Most Read

- Home

- LIVER DIS-EASE AND GALL BLADDER DIS-EASE

- Contacts

- African Wholistics - Medicines, Machines and Ignorance

- African Wholistics -The Overlooked Revolution

- African Holistics - Seduced by Ignorance and Research

- The Children of the Sun-3

- Kidney Stones-African Holistic Health

- The Serpent and the RainBow-The Jaguar - 2

- PART ONE: DIS-EASE TREATMENT AND HEALTH-3

- 'Tortured' and shackled pupils freed from Nigerian Islamic school

- King Leopold's Ghost - Introduction

- PART ONE: DIS-EASE TREATMENT AND HEALTH-4

- PART ONE: DIS-EASE TREATMENT AND HEALTH-2

- PART ONE: DIS-EASE TREATMENT AND HEALTH-5

- African Wholistics - Medicine

- Menopause

- The Black Pharaohs Nubian Pharaohs of Ancient Egypt

- The Mystery System

- PART ONE: DIS-EASE TREATMENT AND HEALTH-6

Who's On Line?

We have 122 guests and no members online

Ad Agency Remote

Articles - Latest

- The Male G Spot Is Real—and It's the Secret to an Unbelievable Orgasm

- Herbs for Parasitic Infections

- Vaginal Care - From Pubes to Lubes: 8 Ways to Keep Your Vagina Happy

- 5 Negative Side Effects Of Anal Sex

- Your Herbs and Spices Might Contain Arsenic, Cadmium, and Lead

- Struggling COVID-19 Vaccines From AstraZeneca, BioNTech/Pfizer, Moderna Cut Incidence Of Arterial Thromboses That Cause Heart Attacks, Strokes, British Study Shows

- Cartilage comfort - Natural Solutions

- Stop Overthinking Now: 18 Ways to Control Your Mind Again

- Groundbreaking method profiles gene activity in the living brain

- Top 5 health benefits of quinoa

- Chromolaena odorata - Jackanna Bush

- Quickly Drain You Lymph System Using Theses Simple Techniques to Boost Immunity and Remove Toxins

- Doctors from Nigeria 'facing exploitation' in UK

- Amaranth, callaloo, bayam, chauli

- 9 Impressive Benefits of Horsetail

- Collagen The Age-Defying Secret Of The Stars + Popular Products in 2025

- Sarcopenia With Aging

- How to Travel as a Senior (20 Simple Tips)

- Everything you need to know about mangosteen